U.S. Agricultural Export Opportunities in Brazil

Contact:

Printer-Friendly PDF (394.64 KB)

Brazil’s consumers have a budding appetite for higher-value food products as the country’s economy recovers from a historic recession and its middle class grows. These key factors provide a promising future for increased U.S. food and agricultural exports to the country. Ranking as the world’s eighth-largest economy and the fifth-largest country, Brazil’s population of 210 million people is predominately urban (86 percent), with a stable middle class. The country’s expanding middle class increased from 12.5 million households to more than 21 million from 2000 to 2016 and is expected to grow to 22.3 million households by 2021.

Nearly 7 million households are in the upper middle class, earning above $50,000 (2005 Purchasing Power Parity [PPP])i in 2016. While the gap between middle income and low income remains significant, the percentage of households earning below $20,000 (2005, PPP) remains mostly unchanged for the past decade. Economically, Brazil is recovering from an eight-quarter-long recession, one of the worst in its history. Politically, the country has undergone recent shifts in leadership. Despite these many challenges, unemployment rates in the country are expected to return to the single-digit levels that existed prior to the recession. This economic recovery, combined with the expanding middle class, signify strong demand and growth in the food sector resulting in opportunities for U.S. food and agricultural exporters.

Global Market Perspective

| Top Brazilian Agricultural Imports from the World | ||||||

| Product | Thousands USD | U.S. Market Share 2016 | ||||

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | ||

| Total Agricultural | 10,719,294 | 11,626,134 | 11,008,773 | 8,671,117 | 10,036,064 | 8% |

| Wheat | 1,757,056 | 2,414,821 | 1,812,324 | 1,216,466 | 1,335,389 | 18% |

| Fresh & Processed Vegetables | 747,448 | 1,010,735 | 901,932 | 837,594 | 1,012,700 | 1% |

| Dairy Products | 795,026 | 783,014 | 665,725 | 622,707 | 840,639 | 8% |

| Fresh & Processed Fruit | 670,398 | 704,186 | 758,272 | 554,983 | 607,420 | 2% |

| Corn | 164,607 | 138,143 | 103,830 | 41,352 | 489,122 | n/a |

| Vegetable Oils | 515,111 | 571,428 | 568,556 | 485,396 | 474,803 | 3% |

| Source: Global Trade Atlas (GTA), BICO HS-6 | ||||||

The Common Market of the South (Mercosur)ii is a free trade agreement between Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and Venezuela that began promoting more fluid movement of goods, services and currency in 1991 and was later amended in 1994. Mercosur provides preferential treatment to the member countries allowing lower and duty-free tariffs while imposing external tariffs on non-member countries. Following implementation of the agreement, Brazil also became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995. Since joining the WTO, Brazil’s agricultural imports have doubled. In 2016, Brazil imported $10 billion of agricultural products. Top imports include wheat, fresh and processed vegetables, dairy products, fresh and processed fruit, corn and vegetable oils. The majority of full-member Mercosur free-trading partners are among Brazil’s top suppliers of agricultural products. In 2016, nearly 50 percent of Brazil’s agricultural imports were supplied by Mercosur countries, while 8 percent of agricultural imports came from the United States. The top suppliers to Brazil were Argentina, the European Union (EU), Uruguay, Paraguay and the United States.

U.S. Exports to Brazil

Since 2000, U.S. agricultural exports to Brazil have grown 231 percent, from $264 million to $872 million in 2016. Brazil is the 22nd largest agricultural export market for the United States with wheat, prepared foods, cotton, dairy products, and feeds and fodders topping the list. Agricultural products with the largest export growth since 1997 include wheat, egg and egg products, roasted coffee and tea. Due to Brazil’s economic recession, U.S. agricultural exports in 2016 were down from the record-setting $1.9 billion in 2013, when U.S. wheat exports skyrocketed due to short supplies and export restrictions in Argentina, Brazil’s traditional wheat supplier.

Agricultural-related products such as ethanol, forest products, distilled spirits and fish products also boosted U.S. export growth to the country. In 2016, the United States exported nearly $502 million of agricultural-related products to Brazil, of which 93 percent was ethanol. The United States supplied 99 percent of Brazil’s ethanol imports in 2016, with sales totaling roughly $467 million. As U.S. ethanol exports to Brazil approach record levels in 2017, Brazil has responded by imposing a tariff-rate quota on ethanol, under which it will apply a 20-percent tariff on all imports over 600 million liters. Brazil’s imports of U.S. ethanol have averaged about 650 million liters (valued at $410 million) annually since 2011. The tariff is expected to affect U.S. ethanol exports to Brazil in years when Brazil experiences drought, or when world sugar prices are high, causing more Brazilian sugar cane to go into sugar instead of ethanol, as was the case in 2016 and 2017. In addition to ethanol, the value of U.S. forest products exports reached more than $21 million in 2016, while distilled spirits and fish products totaled $10 million and $3 million, respectively.

Consumer Trends Create U.S. Opportunities

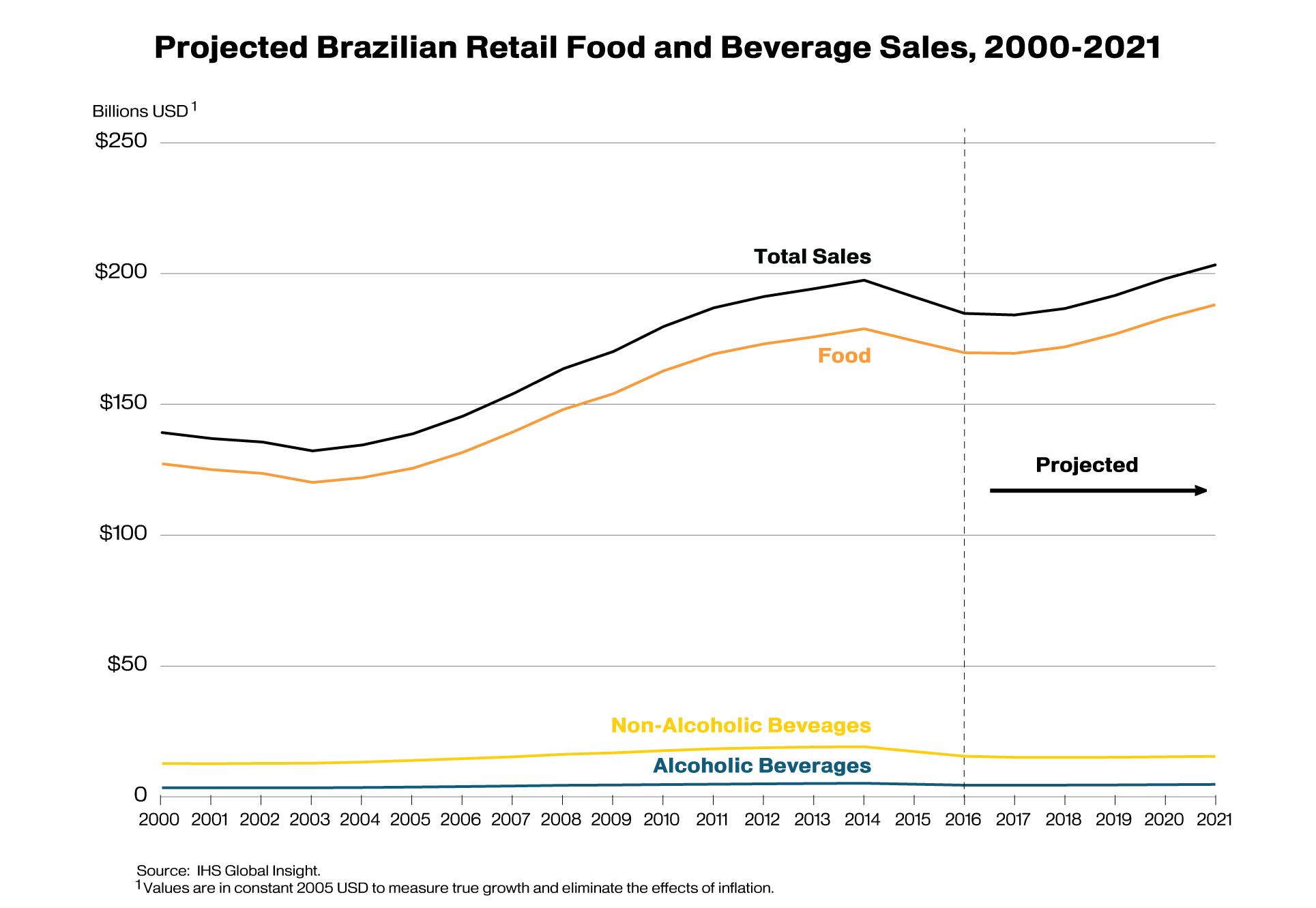

During the peak of the recession in 2015, Brazilian consumers modified their consumption habits to accommodate higher food prices. Retailers and importers began rebranding well-known premium brands to create less-expensive products. The Brazilian Supermarket Association (ABRAS) found that offering “bonus packs” and “price discounts” became important tools for promoting product sales. Although these tools drove sales in 2016, recent consumer trends have shifted towards focusing on the “value of money”. This trend means that consumers are not only interested in better deals, but that the quality of the product plays a more important role when considering a purchase. Trends show that Brazilians are purchasing less in quantity and focusing more on the quality of products. For this reason, long-term projections for retail food and beverage sales, which had dipped from a high in 2014, now indicate growth recovery.

As the Brazilian economy recovers and consumers demand higher-value products, exports of U.S. agricultural products have a promising future. Examples include:

- U.S. Fresh Beef - After a 13-year hiatus, U.S. fresh beef made its return to Brazil in May 2017. Although the United States is competing with Mercosur countries, Brazil’s main suppliers of beef and beef products, the United States is in a great position to target high-end consumers with its fresh beef products.

- U.S. Organic Food - With Brazil’s aging population and shift in consumer trends to healthier food alternatives, U.S. organic food has the potential to prosper. Introducing higher-value products such as organic prepared food options to the Brazilian market addresses both health and sustainability concerns represented in current consumer trends.

- U.S. Alcoholic Beverages - The consumer trend of “value of money” has also contributed to changes in retail sales of alcoholic beverages. Annual sales of alcoholic beverages such as wine and beer are growing at a faster rate than retail food and nonalcoholic beverages.

Socioeconomic Factors

While the most devastating recession in the past 25 years contributed to shifts in consumer trends, the socioeconomic diversity of Brazil’s population also plays a major role in influencing consumer preferences. Brazil’s uneven distribution of income causes a sharp divide in household spending. Although the country is considered “middle-income” by the World Bank, 21.3 million households occupied the middle class in 2016 and more than 43 million households were considered below middle class. Even the middle class is economically stratified. Middle class income distribution is devised mostly of households earning between $20,000 to $30,000; $30,000 to $40,000; and $100,000 to $150,000; with the in-between income levels of $41,000 to $99,000 only contributing to 27 percent of Brazil’s middle class in 2016.

Brazil’s previously noted aging population is also impacting consumer buying patterns as more people are expected to demand healthier food alternatives. Although Brazil does not have a defined age for retirement, in 2016, 8 percent of the population was 65 years or older while 69 percent of the population was in the working age range of 15 to 64 years old. By 2021, it is expected that the 65 years or older population will increase to 10 percent. As more of the population in the retirement age range is expected to leave the workforce, spending habits are also expected to focus on the “value of money”.

Geographic Factors

Location plays another factor in Brazil’s consumer buying trends. Divided into five different regions, the Southeast, South, North, Northeast, and Center-West, Brazil’s middle class households are heavily concentrated in the Southeast region. Much of the Southeast region’s success is due to settling of immigrants and exposure to international businesses through port accessibility. Brazil’s Northeast region offers large opportunities for economic and import growth. Brazil’s Northeast region covers more than 600,000 square miles, roughly the size of Texas, California and Montana combined. This area represents about 19 percent of Brazil’s national territory and houses nearly 26 percent of Brazil’s population. Lower middle class households within the Northeast region have increased demand for imported products due to the growth of private Brazilian and foreign multinational companies’ investment in infrastructure. The region’s demand for higher-value products has opened doors for a variant class of consumers and created a necessity for enhancement of transportation methods.

The Northeast’s largest cities of Recife, Fortaleza and Salvador are situated on the coast and have populations between 2-4 million people. Thanks to investments in infrastructure projects over the last two decades, such as new ports, shipyards, airports and a refinery, the economy in this region is growing faster than the rest of Brazil, with the region’s GDP larger than that of most Latin American countries. Their coastal location and northern geography make them very accessible to U.S. maritime cargo shipments leaving southern U.S. ports. An upsurge in hotel and leisure investment is also spurring increased domestic and international tourism to the region and with it the demand for higher quality, consumable foodstuffs.

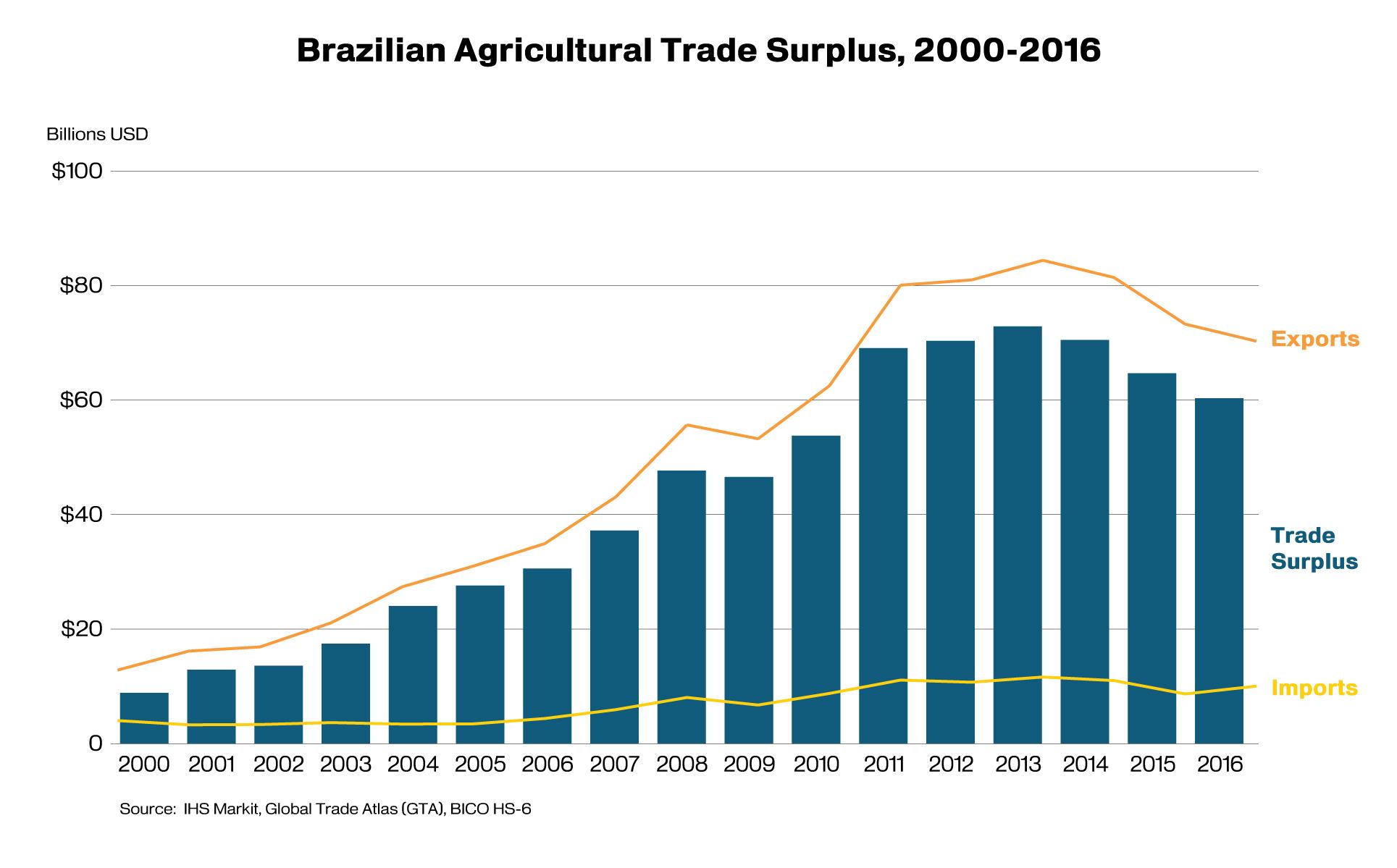

Free Trade Agreements and U.S. Competition

Despite the evolution of the economy in the past decade, Brazil still relies on agricultural exports to drive economic growth. Since 2000, Brazil’s global agricultural trade surplus increased from $8.8 billion to $60.3 billion in 2016. In 2016, Brazil exported $70.3 billion in agricultural products to the world. China, the EU, the United States, Japan and Iran are among the top export destinations. Top agricultural exports include soybeans, sugar, poultry meat, beef and beef products, soybean meal, unroasted coffee, corn, fruit and vegetable juices, tobacco, and pork and pork products. For 2016, Brazil was the world’s second largest exporter of soybeans after the United States. While export quantities have increased, the value of Brazil’s soybean exports has been lower the past couple of years, with the decline in export value largely attributed to lower commodity prices.

Although operating on an agricultural trade surplus, Brazil faces many infrastructural issues that hinder agricultural production and exports. Brazil’s economic growth relies heavily on consumption. However, given an outflow of capital, the investment needed to expand and maintain infrastructure has been neglected. In 2001, Goldman Sachs coined the acronym BRIC to define Brazil, Russia, India and China as countries with the largest and fastest emerging market economies. According to Euromonitor, of the BRIC countries, Brazil currently invests less than 20 percent of its GDP in infrastructure, 3 percent less than the BRIC average. Without GDP allocation in infrastructure, both agricultural exports and imports in Brazil may suffer due to higher transportation and production costs.

In efforts to continue its road to recovery, Brazil is actively seeking free trade agreements (FTAs) to boost exports, improve weak public finances, jump-start stagnant economic growth and strengthen consumer spending. One such FTA Brazil is negotiating is with the EU, as part of Mercosur. U.S. food and beverages directly compete with European products and face barriers including higher entry costs, the stronger U.S. dollar competing with the weaker Brazilian real and the local tariff system. As the Brazilian market is developed compared to other Latin American nations, U.S. producers must cater their products to offset existing barriers and preferences. Producers must make their products appealing to accommodate high-end labeling, transportation issues and accessibility of small retail stores.

The United States is the second largest supplier of processed foods to Brazil, directly competing with the EU. In 2016, Brazil imported only 15 percent of its processed food from the United States while importing over double that amount from the EU at 35 percent. The United States ranks as the seventh largest supplier of beer and wine to Brazil in 2016. Brazilian imports of beer and wine from the United States have marginally increased from nearly $1.3 million in 2000 to just over $4.7 million in 2016. The United States is the largest supplier of healthy snack options to Brazil such as mixes of nuts and fruit, while the EU ranks as the third largest supplier.

While the EU and Mercosur countries pose direct competition for the United States in Brazil, the nation’s economic recovery within the next five years offers opportunities for U.S. exporters of agricultural products. By 2021, IHS Global Insight forecasts that Brazil’s rural population is expected to decrease by 2 percent while the urban population is expected to grow by 5 percent. Along with an aging population and growth in the labor force, consumers will continue to focus on the quality of food versus the quantity. Exposure of urban societies to larger scale retail markets will drive promotion potential and increase exposure of healthier food alternatives along with increased demand for high-end retail choices and imported products.